Metabolic syndrome isn’t just a label doctors use to scare patients. It’s a real, measurable cluster of warning signs that tell you your body is struggling to manage energy. And at the heart of it are three simple things: how big your waist is, how high your triglycerides are, and how well your body controls blood sugar. If two or more of these are off, your risk for heart disease and type 2 diabetes jumps dramatically. This isn’t about being overweight-it’s about where the fat is stored, how your liver processes fat, and how your cells respond to insulin.

What Exactly Is Metabolic Syndrome?

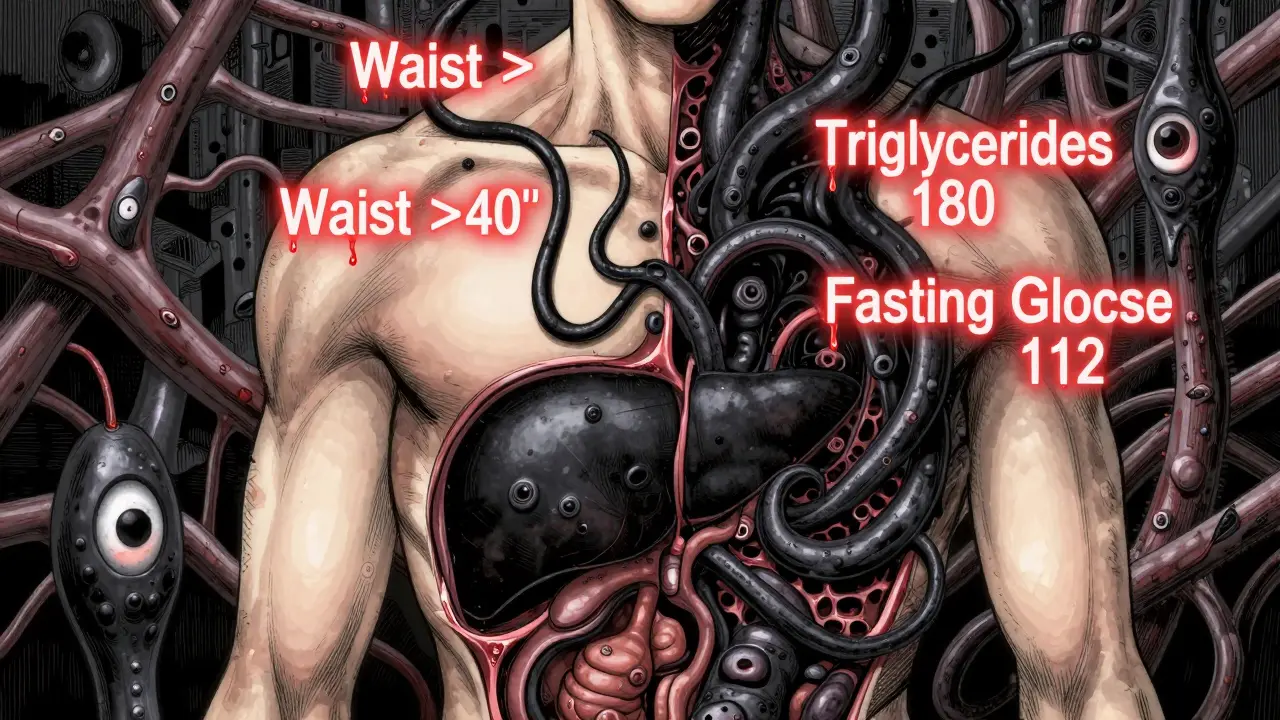

Metabolic syndrome is defined by the presence of at least three out of five specific abnormalities. These aren’t random symptoms-they’re hard numbers backed by decades of research from the American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health, and the International Diabetes Federation. The five criteria are: waist size above 40 inches for men or 35 inches for women, triglycerides at 150 mg/dL or higher, HDL cholesterol below 40 mg/dL for men or 50 mg/dL for women, blood pressure at 130/85 mm Hg or higher, and fasting blood glucose of 100 mg/dL or more. You don’t need to have diabetes to meet the criteria. Even prediabetes-blood sugar between 100 and 125 mg/dL-counts.

According to data from the 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, nearly 35% of U.S. adults have metabolic syndrome. That’s one in three. And the numbers climb with age. By 60, nearly half of people meet the criteria. The scary part? Most don’t know they have it. There are no obvious symptoms. No pain. No dizziness. Just quietly rising numbers on lab reports and tape measures.

Why Waist Size Matters More Than Weight

It’s not about the scale. It’s about the tape. A man with a 38-inch waist and a BMI of 26 might be perfectly healthy. A man with a 42-inch waist and the same BMI? He’s at high risk. That’s because abdominal fat-fat that wraps around your organs-isn’t just storage. It’s active tissue that releases chemicals that disrupt metabolism.

When fat cells in the belly grow too large, they start spilling out inflammatory signals like tumor necrosis factor-alpha and resistin. These chemicals interfere with insulin’s ability to tell muscle and liver cells to take up glucose. The result? Your pancreas pumps out more insulin to compensate. Over time, your cells stop listening. That’s insulin resistance. And insulin resistance is the engine that drives the rest of metabolic syndrome.

Research in Circulation found that every 4-inch increase in waist size raises heart disease risk by 10%, even after adjusting for total body weight. That’s why the American Heart Association now says waist circumference is a better predictor of heart risk than BMI. A woman with a 36-inch waist and normal BMI still has double the risk of heart disease compared to someone with a 28-inch waist.

Triglycerides: The Hidden Fat That Clogs Arteries

Triglycerides are the most common type of fat in your blood. When you eat more calories than your body needs-especially from sugar and refined carbs-your liver turns the excess into triglycerides and ships them out as VLDL particles. These particles float in your bloodstream, and when they’re too numerous, they contribute to plaque buildup in your arteries.

The cutoff for normal is 150 mg/dL. But here’s the catch: risk doesn’t suddenly spike at 151. Studies from the American Heart Association show that even levels between 150 and 199 mg/dL increase cardiovascular risk. Once you hit 200 mg/dL, your risk jumps again. And if you’re above 500 mg/dL, you’re at risk for pancreatitis, not just heart disease.

What makes this worse? Insulin resistance. When your cells don’t respond to insulin, your liver keeps making triglycerides instead of slowing down. And those high triglycerides? They make insulin resistance even worse. It’s a loop: insulin resistance raises triglycerides, and high triglycerides make insulin resistance worse. This is called lipotoxicity-fat poisoning your own cells.

One study in Diabetes Care showed that people with triglycerides over 200 mg/dL had 60% higher insulin resistance than those with levels under 100 mg/dL-even if their weight was normal. That’s why lowering triglycerides isn’t just about heart health. It’s about fixing your metabolism.

Glucose Control: The Early Warning Sign

Fasting blood glucose of 100 mg/dL or higher means your body is already struggling to manage sugar. That’s not diabetes. That’s prediabetes. And according to the Diabetes Prevention Program, people with prediabetes have a 5% to 10% chance of developing full-blown type 2 diabetes every year. Without intervention, most will progress within a decade.

The problem starts in muscle cells. Insulin normally tells these cells to open their doors and let glucose in. But with insulin resistance, those doors stay shut. Your liver, meanwhile, keeps making glucose even when you’re not eating. So your blood sugar rises. Your pancreas responds by pumping out more insulin. Eventually, it burns out. That’s when type 2 diabetes kicks in.

What’s alarming? Eighty-five percent of people with type 2 diabetes already had at least one component of metabolic syndrome before diagnosis. Half met all the criteria. That means the damage starts years before diagnosis. By the time you’re told you have diabetes, your blood vessels, kidneys, and nerves have already been exposed to high sugar for years.

The Cycle: How Waist, Triglycerides, and Glucose Feed Each Other

This isn’t three separate problems. It’s one broken system. Abdominal fat triggers insulin resistance. Insulin resistance tells the liver to make more triglycerides. High triglycerides make muscle cells less responsive to insulin. That forces the liver to make even more glucose. Blood sugar rises. Fat storage increases. The cycle tightens.

Think of it like a car with a stuck gas pedal. The engine (your liver) keeps revving, even when you don’t need more power. The fuel (glucose and fat) piles up. The system overheats. That’s metabolic syndrome.

Research from Washington University in St. Louis showed that when people with metabolic syndrome lost 7% of their body weight, their triglycerides dropped by 30%, insulin sensitivity improved by 40%, and fasting glucose fell by 15%. The changes weren’t just statistical-they were dramatic. And they happened before any medication was used.

How to Break the Cycle

The good news? Metabolic syndrome is reversible. You don’t need surgery. You don’t need expensive drugs. You need to change how you move and what you eat.

Move more: Aim for at least 150 minutes of brisk walking, cycling, or swimming per week. Research shows that even 30 minutes a day, five days a week, reduces waist size and improves insulin sensitivity. Strength training twice a week helps too-muscle burns glucose even when you’re not moving.

Eat smarter: Cut added sugars. That means soda, candy, pastries, and even “healthy” granola bars. A 2018 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that people who followed a Mediterranean diet-rich in olive oil, vegetables, nuts, and fish-reduced their risk of heart attack by 30%. Fiber is key. Aim for 30 grams a day. It slows sugar absorption and feeds good gut bacteria.

Limit alcohol: One drink a day for women, two for men. Alcohol floods the liver with fat and raises triglycerides. Even moderate drinking can undo progress.

Get sleep and manage stress: Poor sleep and chronic stress raise cortisol, which increases abdominal fat and blood sugar. Just one night of bad sleep can reduce insulin sensitivity by 25%.

Medications like metformin, fibrates, or statins may help, but they’re not replacements for lifestyle change. The NIH says weight loss is still the most effective way to reverse all five components of metabolic syndrome. Losing just 5% to 10% of your body weight can normalize triglycerides, lower blood pressure, and bring glucose back into range.

What’s Next? The Future of Detection

New tools are emerging. The TyG index-calculated from fasting triglycerides and glucose-is gaining traction as a simple, low-cost way to estimate insulin resistance. A score above 8.5 suggests you’re at risk. Some clinics are already using it alongside traditional markers.

Researchers are also looking at gut bacteria. A 2023 study in Nature Medicine found specific microbial patterns in people with metabolic syndrome that differ from healthy individuals. Future treatments might involve probiotics or targeted diets to reshape the microbiome.

But none of this matters if we ignore the basics. You don’t need a fancy test to know if you’re at risk. Measure your waist. Get your triglycerides checked. Know your fasting glucose. If two of these are out of range, don’t wait for a diagnosis. Start changing your habits now.

Can you have metabolic syndrome without being overweight?

Yes. While abdominal fat is the main driver, some people-especially those of South Asian, East Asian, or Hispanic descent-develop metabolic syndrome at lower body weights. A person with a normal BMI but a waist over 35 inches (women) or 40 inches (men) can still meet diagnostic criteria. Genetics, diet, and activity levels play a big role.

Is metabolic syndrome the same as prediabetes?

No. Prediabetes is one component of metabolic syndrome-specifically, elevated fasting glucose. But metabolic syndrome includes at least three of five factors: waist size, triglycerides, HDL, blood pressure, and glucose. You can have prediabetes without the other four, or you can have metabolic syndrome without meeting the glucose threshold for prediabetes.

Can losing weight reverse metabolic syndrome?

Yes. Studies show that losing 5% to 10% of your body weight can normalize triglycerides, improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood pressure, and reduce waist size. In the Diabetes Prevention Program, lifestyle changes cut diabetes risk by 58% over three years. Weight loss is the most effective treatment available.

Do I need medication if I have metabolic syndrome?

Not always. Lifestyle changes are the first and most important step. Medications like metformin (for glucose), fibrates (for triglycerides), or ACE inhibitors (for blood pressure) may be added if your numbers don’t improve after 3-6 months of consistent lifestyle changes. But drugs don’t fix the root cause-only weight loss and movement do.

How often should I get tested for metabolic syndrome?

If you’re over 40, or have a family history of diabetes or heart disease, get checked every year. If you’re younger but have a waist over 35 inches (women) or 40 inches (men), get tested every 2 years. A simple blood test and tape measure can catch it early. Don’t wait for symptoms-they won’t come until it’s too late.