Every year, millions of people take medications that can silently damage their hearing. Many never know it’s happening until it’s too late. Ototoxic medications - drugs that harm the inner ear - are often lifesaving, but they come with a hidden cost: permanent hearing loss or balance problems. This isn’t rare. It’s common. And it’s mostly preventable.

What Makes a Drug Ototoxic?

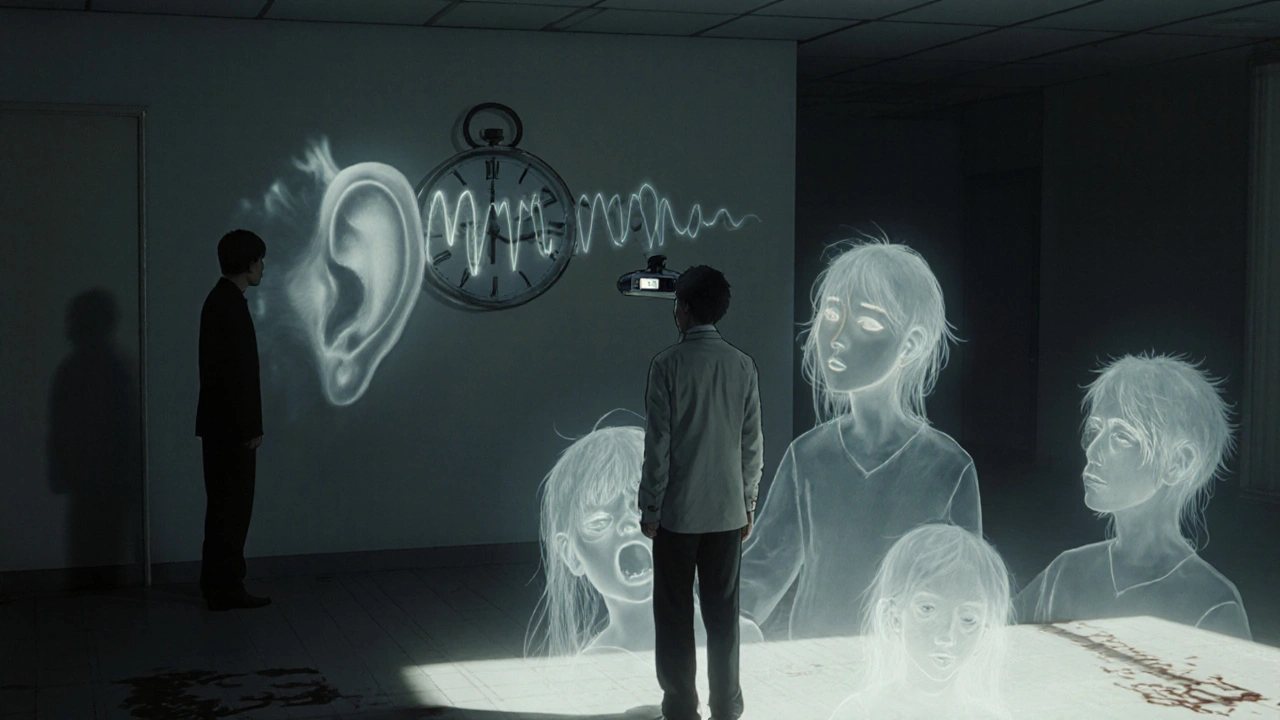

Not all drugs affect hearing. But some do - and they do it in ways most doctors don’t routinely check for. Ototoxicity means damage to the cochlea (the hearing part) or the vestibular system (the balance part) of the inner ear. The damage happens because these drugs kill the tiny hair cells inside your ear. These cells don’t grow back. Once they’re gone, the hearing loss is permanent.

Over 600 prescription drugs are known to be ototoxic, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. The biggest culprits fall into three main groups: aminoglycoside antibiotics, platinum-based chemotherapy drugs, and some antidepressants.

Take gentamicin, for example. Used to fight serious infections like sepsis or drug-resistant tuberculosis, it can cause hearing loss in 20% to 63% of patients who take it for more than a week. That’s not a small risk - that’s a major one. And it doesn’t always show up right away. Often, the first sign is tinnitus - a ringing, buzzing, or hissing sound in the ears - before hearing starts to fade.

How Cisplatin Destroys Hearing - And Why It’s So Dangerous

Cisplatin is one of the most effective chemotherapy drugs for treating cancers like testicular, ovarian, and lung cancer. But it’s also one of the most damaging to hearing. Between 30% and 60% of patients who receive cisplatin develop some level of hearing loss. In 18% of cases, it’s severe or profound.

What makes cisplatin worse than other ototoxic drugs? It doesn’t just damage your ears during treatment - it sticks around. Cisplatin builds up in the cochlea and can keep causing damage for months after your last dose. That’s why hearing loss often gets worse even after chemotherapy ends.

Standard hearing tests - the kind done in most doctor’s offices - only check up to 4,000 Hz. But cisplatin attacks the high frequencies first - 6,000 Hz, 8,000 Hz, even 12,000 Hz. That means you could lose the ability to hear birds chirping, children’s voices, or the word “s” in speech long before your doctor notices anything on a routine test.

One patient on Reddit shared: “After my third cisplatin cycle, I noticed I couldn’t hear my daughter’s voice clearly in noisy rooms. My oncologist said my hearing was fine - until I got a high-frequency test. I’d lost 50% of my hearing at 8,000 Hz.”

Other Ototoxic Drugs You Might Not Realize Are Risky

It’s not just antibiotics and chemo. Some everyday medications can also hurt your hearing.

- Other aminoglycosides: Tobramycin, amikacin, streptomycin - all carry similar risks. Streptomycin, first linked to hearing loss in the 1940s, still causes permanent damage in up to 50% of TB patients in high-risk areas.

- Loop diuretics: Furosemide (Lasix) and bumetanide, used for heart failure or fluid retention, can cause temporary hearing loss, especially at high doses or when combined with aminoglycosides.

- Antidepressants: Tricyclics like amitriptyline and SSRIs like sertraline (Zoloft) and fluoxetine (Prozac) have been linked to tinnitus and, in rare cases, hearing loss. The mechanism isn’t fully understood, but it’s real enough that patients report these symptoms consistently.

- Aspirin and NSAIDs: High doses of aspirin (over 8 grams daily) or prolonged use of ibuprofen can cause temporary ringing or muffled hearing. This usually reverses when you stop taking them.

Carboplatin and oxaliplatin - other chemo drugs - are much safer for hearing. Carboplatin causes hearing loss in only 5% to 15% of patients. In some cases, doctors switch from cisplatin to carboplatin to protect hearing, especially in children. But that’s not always possible - cisplatin is more effective against certain tumors.

Why Routine Hearing Tests Miss the Problem

Most people think, “If my hearing is fine, I’m safe.” But that’s a dangerous assumption.

Standard audiograms test frequencies up to 4,000 Hz. That’s what your doctor checks when you say, “I can’t hear people talking.” But ototoxic damage starts at 8,000 Hz and above - frequencies you don’t need for speech, but that matter for clarity, balance, and quality of life.

Without high-frequency testing, you’re flying blind. A 2023 study found that 62% of cisplatin-treated children had significant hearing loss at 8,000 Hz - but only 12% were flagged by standard testing.

Even worse, many oncologists and infectious disease specialists don’t know to refer patients to audiologists. Only 45% of U.S. cancer centers have formal ototoxicity monitoring programs. That means over half of patients are being treated without any hearing checks at all.

How to Monitor Ototoxicity - The Right Way

Early detection saves hearing. Here’s what actually works:

- Baseline audiogram before treatment: Get a full hearing test - including 8,000 Hz and 12,000 Hz - before starting cisplatin, gentamicin, or any high-risk drug. Keep a copy.

- High-frequency audiometry during treatment: Test every 1-2 weeks during cisplatin cycles, or after each dose of aminoglycosides. Don’t wait for symptoms.

- Otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing: This test measures the sound your inner ear produces in response to clicks. It detects hair cell damage before you even notice hearing loss - and it’s 25% more sensitive than standard tests.

- Vestibular testing if dizzy: If you feel unsteady, have vertigo, or can’t walk in the dark, ask for balance testing. Aminoglycosides damage both hearing and balance.

- Genetic screening for high-risk patients: If you or a family member lost hearing after taking gentamicin or streptomycin, ask about genetic testing for m.1555A>G or m.1494C>T mutations. These make you 100 times more likely to suffer hearing loss from these drugs.

Patients who get this kind of monitoring reduce their risk of severe hearing loss by 30% to 50%, according to Cleveland Clinic data.

What You Can Do - As a Patient or Caregiver

If you’re about to start cisplatin, gentamicin, or another high-risk drug:

- Ask your doctor: “Is this drug ototoxic? Do you monitor hearing during treatment?”

- Insist on a baseline hearing test before treatment starts - and make sure it includes high frequencies.

- Request a referral to an audiologist who specializes in ototoxicity monitoring.

- Track symptoms: Ringing in the ears? Muffled hearing? Dizziness? Report them immediately - don’t wait.

- If you’re treating a child: Pediatric hearing loss from chemo can delay language development. Early intervention is critical.

Don’t assume your doctor knows. Many don’t. You have to be your own advocate.

New Hope: Otoprotective Treatments and Future Advances

There’s good news. Science is catching up.

In November 2022, the FDA approved sodium thiosulfate (Pedmark) to reduce cisplatin-induced hearing loss in children with liver cancer. In trials, it cut hearing loss risk by 48%. It’s now standard for pediatric patients in many centers.

Researchers are testing antioxidants like N-acetylcysteine to protect against aminoglycoside damage. Early results are promising.

Smartphone apps are being developed to let patients test their own hearing at home using high-frequency tones. One study showed these apps could detect early hearing loss with 75% accuracy - making monitoring accessible even in rural areas.

And the Ototoxicity Working Group is updating its guidelines in 2024 to include genetic screening recommendations - a major step toward personalized care.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Over 15 million Americans take ototoxic drugs each year. Cisplatin alone is given to more than 500,000 cancer patients annually. The cost of untreated hearing loss - hearing aids, speech therapy, lost jobs, social isolation - exceeds $1 billion per year in the U.S.

But this isn’t just about money. It’s about quality of life. A man on gentamicin described his tinnitus as “a siren that never stops.” A child with untreated hearing loss from cisplatin struggles to learn speech. A woman can’t hear her grandchildren laugh.

These aren’t side effects. They’re preventable injuries.

There’s no excuse anymore. We know which drugs are dangerous. We know how to catch the damage early. We have tools to protect hearing. The only thing missing is consistent action.

Ask for the test. Demand the monitor. Save your hearing before it’s gone for good.

Can ototoxic hearing loss be reversed?

No, ototoxic hearing loss is permanent. The hair cells in your inner ear don’t regenerate. Once they’re damaged by drugs like cisplatin or gentamicin, the hearing loss is irreversible. That’s why early detection through high-frequency audiometry is critical - it allows doctors to adjust treatment before damage becomes severe.

Do all antibiotics cause hearing loss?

No. Only certain classes, primarily aminoglycosides like gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin, carry high ototoxic risk. Other antibiotics like penicillin, amoxicillin, and even vancomycin have very low or negligible risk. Vancomycin, for example, causes hearing loss in only 5-10% of patients, compared to 20-63% for gentamicin.

How often should I get my hearing tested if I’m on cisplatin?

You should have a baseline hearing test before treatment starts. Then, get tested after each chemotherapy cycle - typically every 1 to 2 weeks during treatment. Testing should include frequencies up to 8,000 Hz or 12,000 Hz, not just the standard 4,000 Hz. Otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing can also be used between visits for earlier detection.

Is there a genetic test for ototoxicity risk?

Yes. Two mitochondrial DNA mutations - m.1555A>G and m.1494C>T - make people extremely sensitive to aminoglycoside antibiotics. People with these mutations have a 100-fold higher risk of permanent hearing loss after just one dose. Genetic testing is recommended if you or a close family member had sudden hearing loss after taking gentamicin or streptomycin.

Can I still take cisplatin if I’m worried about hearing loss?

Yes - but only with proper monitoring. Cisplatin is highly effective against many cancers. The key is to combine it with high-frequency audiometry and, if eligible, otoprotective drugs like sodium thiosulfate (Pedmark). Many patients keep their hearing intact with careful management. Never refuse life-saving treatment - but always ask for hearing protection.

What should I do if I notice ringing in my ears during treatment?

Report it immediately. Tinnitus is often the first sign of ototoxic damage. Don’t wait until your next appointment. Contact your oncologist or infectious disease specialist right away. Request a high-frequency hearing test. Early intervention can prevent the ringing from turning into permanent hearing loss.

8 Comments

Chris Ashley

November 14, 2025 AT 02:31 AMMy uncle got deaf in one ear after a round of gentamicin for a bad lung infection. Doc said it was 'rare'-turns out he didn't know jack about ototoxicity. Now he can't hear his grandkids call him 'Papa.' Don't let this happen to you.

Nathan Hsu

November 15, 2025 AT 11:24 AMIndia has a massive TB burden, and streptomycin is still used everywhere-especially in rural clinics where audiologists are nonexistent. I’ve seen patients lose hearing after one course, and no one even blinks. We need awareness campaigns, not just posters in hospitals. This is a silent epidemic.

Ashley Durance

November 17, 2025 AT 00:33 AMLet’s be real-most oncologists don’t care about hearing. They’re focused on tumor shrinkage. The fact that 62% of pediatric cisplatin patients go undetected by standard audiograms isn’t negligence-it’s systemic failure. And yes, you can blame the FDA for not mandating monitoring until 2024. Meanwhile, kids are falling behind in school because no one tested their 8kHz thresholds. This isn’t a ‘maybe’-it’s a documented crisis.

Scott Saleska

November 18, 2025 AT 01:18 AMI’m a pharmacist and I see this all the time. Patients on Zoloft come in saying they hear a constant buzz, and their doctor says, ‘It’s just anxiety.’ But there’s solid literature linking SSRIs to tinnitus-even if it’s rare. And when you combine them with NSAIDs? Double whammy. You need to track every single symptom, no matter how small. I’ve had patients reverse the ringing just by switching antidepressants. It’s not magic-it’s pharmacology.

Ryan Anderson

November 19, 2025 AT 20:01 PMJust had my third cisplatin cycle last week. Got the high-frequency test yesterday-lost 40% at 8kHz. My oncologist was shocked I even asked for it. 🥺 I printed out the Cleveland Clinic guidelines and handed them to him. He apologized. Now I’m getting Pedmark next cycle. 🙌 You don’t have to be a hero-you just have to be prepared.

Eleanora Keene

November 21, 2025 AT 11:16 AMMy mom is on gentamicin right now for a stubborn infection. I didn't know any of this until I read your post. I'm scheduling her baseline test tomorrow. Thank you for writing this. I'm sharing it with her entire care team. If we can save even a little bit of her hearing, it's worth it.

Don Ablett

November 22, 2025 AT 20:31 PMThe absence of routine high-frequency audiometry in standard clinical practice represents a significant gap in patient safety protocols. The persistence of ototoxic damage post-treatment, particularly with cisplatin, necessitates longitudinal auditory monitoring. It is regrettable that such interventions remain discretionary rather than mandatory. Further research into otoprotective agents should be prioritized by regulatory bodies.

Kevin Wagner

November 24, 2025 AT 14:28 PMTHIS. IS. NON-NEGOTIABLE. If your doctor doesn’t know about OAE testing or genetic screening for m.1555A>G, fire them. Your hearing isn’t a side note-it’s your connection to the world. I’ve seen people lose their marriages because they couldn’t hear their partner’s voice. Don’t wait until you’re drowning in silence. Demand the test. Bring the paper. Show up like your life depends on it-because it does. 🚨🔥