Opioid Risk Assessment Tool

Personal Risk Assessment

This tool helps assess your personal risk of opioid-induced respiratory depression based on clinical factors. Remember: this is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice.

Age

Gender

Previous Opioid Use

Medication Interactions

Pre-existing Conditions

0%

Risk Level

Low risk

Recommended Actions

- Monitor breathing and responsiveness for at least 2 hours after each opioid dose

- Keep naloxone (Narcan) accessible if at moderate or high risk

- Never mix opioids with alcohol or sedatives without medical supervision

- Speak to your doctor about alternative pain management options

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression?

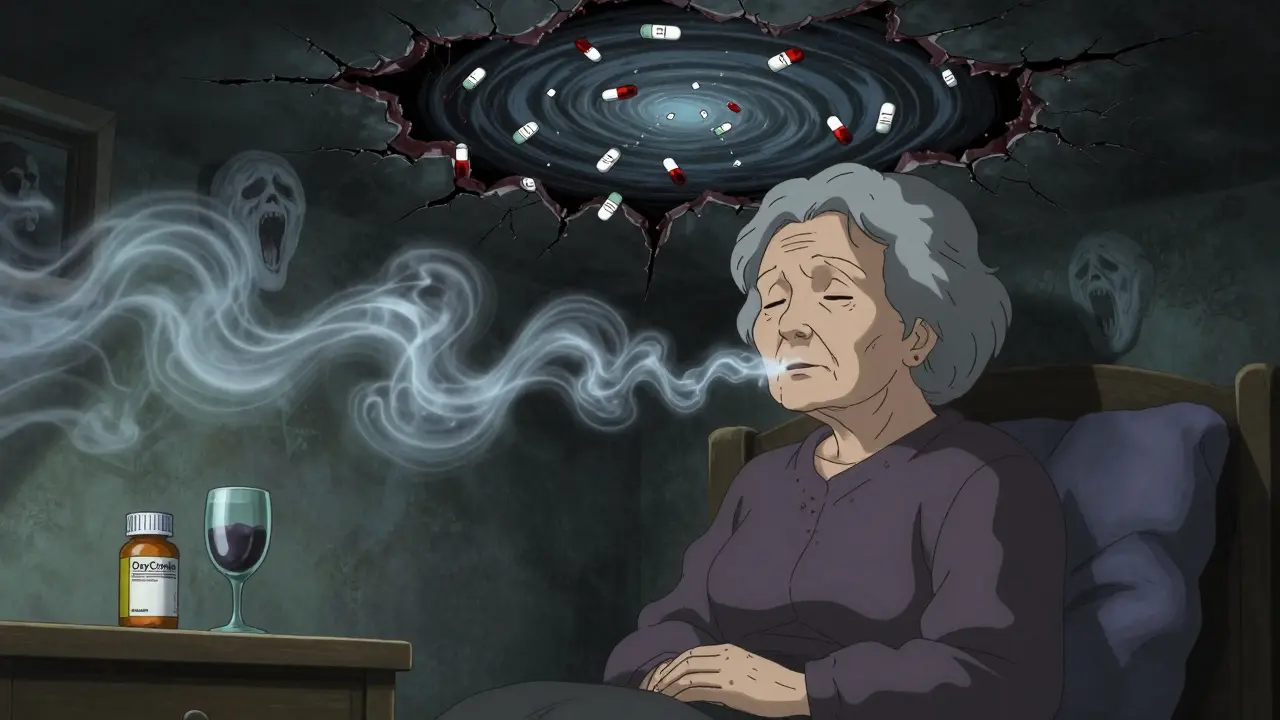

Respiratory depression from opioids isn’t just slow breathing-it’s your body shutting down the automatic system that keeps you alive. When opioids bind to receptors in your brainstem, they quiet the signals that tell your lungs to breathe. This isn’t a side effect you can ignore. It’s a silent killer that can turn a routine painkiller dose into a life-or-death situation.

Doctors call it opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD). The clinical definition is simple: a breathing rate below 8 to 10 breaths per minute, paired with oxygen saturation dropping below 85%. But here’s what’s dangerous: you might not notice it until it’s too late. Someone on opioids can look fine-maybe even sleeping peacefully-while their carbon dioxide levels climb dangerously high. Supplemental oxygen can hide this. Their skin might not turn blue. Their pulse might still be strong. But inside, their brain is suffocating.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just people using heroin or street opioids. The biggest danger comes from prescribed medications. If you’re new to opioids-never taken them before-you’re 4.5 times more likely to suffer respiratory depression than someone who’s been on them for years. Older adults, especially over 60, face a 3.2 times higher risk. Women are 1.7 times more vulnerable than men, even when given the same dose.

But the real killer? Mixing opioids with other drugs. Benzodiazepines like Xanax or Valium, sleep aids like Ambien, alcohol, or even some muscle relaxants turn a risky situation into a deadly one. When opioids and these CNS depressants combine, the risk of respiratory depression jumps 14.7 times. That’s not a small increase. That’s a red alert.

People with lung disease, sleep apnea, obesity, or kidney/liver problems are also at higher risk. Their bodies can’t clear the drugs as quickly. Even a standard dose can build up to toxic levels over time.

The 7 Critical Signs You Must Recognize

Early detection saves lives. Here are the real, observable signs-not textbook definitions, but what you’ll actually see in a hospital room or at home:

- Shallow, slow breathing-less than 8 breaths per minute. Count for 15 seconds and multiply by 4. If it’s 7 or lower, it’s an emergency.

- Irregular breathing patterns-long pauses between breaths, then sudden gasps. This isn’t normal sleep breathing. It’s the brain losing control.

- Extreme drowsiness or unresponsiveness-you can’t wake them up with voice or light touch. They don’t respond to pain stimuli.

- Confusion or disorientation-they don’t know where they are, who you are, or what time it is. This isn’t just tiredness.

- Bluish lips or fingertips-a late sign, but a clear one. Cyanosis means oxygen is critically low.

- Slow heart rate-not fast. Slow. Below 60 beats per minute. Opioids depress the nervous system, and that includes the heart.

- Nausea and vomiting-present in 65% of cases. It’s not just stomach upset. It’s a sign your brainstem is being affected.

Don’t wait for all seven. Even one or two, especially slow breathing and unresponsiveness, should trigger immediate action.

Why Pulse Oximetry Alone Isn’t Enough

Hospitals rely on pulse oximeters to track oxygen levels. But here’s the problem: if someone is on supplemental oxygen, their oxygen saturation might stay at 95% even while carbon dioxide builds up to lethal levels. That’s called hypercapnic respiratory failure. The oximeter says everything’s fine. But the patient is slowly drowning in their own CO2.

Capnography-the device that measures carbon dioxide in exhaled breath-is the gold standard when oxygen is being used. It catches trouble 94% of the time, compared to 89% for pulse oximetry alone. That’s why leading hospitals now use both together for high-risk patients.

And here’s the shocking truth: most patients aren’t monitored continuously. A study found that patients checked every four hours are unmonitored 96% of the time. That’s 23 hours and 36 minutes of silence between checks. In that time, a person can go from breathing normally to stopping breathing entirely.

What Happens If It’s Not Treated?

Untreated respiratory depression doesn’t just cause discomfort. It causes brain damage. When your brain doesn’t get enough oxygen for more than a few minutes, neurons start dying. After 10 minutes without oxygen, permanent damage is likely. After 15, survival becomes rare.

Even if the person survives, they may face long-term cognitive issues-memory loss, trouble concentrating, slowed thinking. For older adults, this can mean losing independence. For younger patients, it can derail careers and relationships.

And it’s preventable. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) classifies severe respiratory depression from opioids as a “never event.” That means if it happens in a hospital, they don’t get paid for treating the complications. They’re fined up to 3% of their reimbursement. This isn’t theoretical. It’s real money. And it’s forcing hospitals to change.

How It’s Treated-and Why Naloxone Isn’t Always the Answer

Naloxone (Narcan) reverses opioid effects. It’s the lifesaver. But it’s not a magic bullet. Giving too much too fast can yank the opioid away too quickly, causing sudden, violent withdrawal: vomiting, seizures, heart rhythm problems, and intense pain. For cancer patients relying on opioids for comfort, this is cruel.

The trick? Titrate. Give small doses slowly. Watch the breathing. Stop when it improves. Don’t chase normal breathing if the patient is stable. Over-treatment can be as dangerous as under-treatment.

For non-opioid causes-like barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or alcohol-naloxone does nothing. That’s why knowing what the person took matters. If they took a sleeping pill with alcohol, naloxone won’t help. They need airway support, oxygen, and sometimes mechanical ventilation.

What Hospitals Are Doing Right-and Where They’re Failing

Some hospitals have cut respiratory depression cases by 47%. How? Three things:

- Continuous monitoring with capnography and pulse oximetry for high-risk patients

- Pharmacist-led dosing-no more automatic prescriptions

- Training every nurse and aide to recognize the signs

But here’s the gap: only 22% of U.S. hospitals follow all the safety guidelines. Community hospitals? Just 14%. That’s not a technical problem. It’s a culture problem. Nurses are overworked. Alarms go off constantly-68% of units suffer from alarm fatigue. People stop listening.

And only 31% of hospitals use validated risk assessment tools. Most still rely on guesswork: “They seem okay.” That’s not good enough.

What You Can Do-Before, During, and After

If you or a loved one is prescribed an opioid:

- Ask: “Is this necessary? Can we try something else first?”

- Know your risk: Are you over 60? Female? On other sedatives? Never taken opioids before? If yes, you’re in the danger zone.

- Never mix: No alcohol, no sleeping pills, no anxiety meds unless your doctor says it’s safe-and even then, watch closely.

- Monitor for 2 hours after each dose: Especially the first few times. Check breathing. Check responsiveness.

- Have naloxone on hand: If you’re at high risk, ask your doctor for a prescription. Keep it accessible. Know how to use it.

- Speak up: If someone looks drowsy, breathing slowly, or can’t be woken, call 911 immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t assume they’ll wake up on their own.

The Future: Safer Opioids and AI Monitoring

Researchers are working on new opioids that relieve pain without suppressing breathing. One class, called biased mu-opioid receptor agonists, is in Phase III trials. Early results show promise-pain relief without the respiratory risk.

Meanwhile, AI-powered monitors are getting smarter. New systems can predict respiratory depression 15 minutes before it happens by analyzing subtle changes in breathing patterns, heart rate, and movement. The FDA approved the first Opioid Risk Calculator in January 2023. It uses 12 factors-age, weight, kidney function, medication history-to give a personalized risk score.

But tech alone won’t fix this. People have to pay attention. Nurses have to be trained. Families have to be involved. The tools exist. The knowledge exists. What’s missing is consistent action.

9 Comments

Arlene Mathison

January 21, 2026 AT 00:21 AMI can't believe how many people still think opioids are 'just painkillers.' My mom was on them after her hip surgery and nearly died because the nurses didn't check her breathing for 5 hours. She was fine one minute, then unresponsive the next. I kept begging them to monitor her properly. They said 'she looks peaceful.' Peaceful? She was dying. I'm so glad this post laid out the signs so clearly. If you're on opioids, don't trust 'looks fine.' Count breaths. Touch their shoulder. Wake them up. Don't wait for blue lips.

pragya mishra

January 21, 2026 AT 20:44 PMThis is why I refuse to let my parents take anything stronger than ibuprofen. They're both over 65 and on blood pressure meds. The hospital told them Vicodin was 'safe'-safe for who? The pharmacy? The insurance company? I told them if they take it, I'm moving in. No more 'I'm fine' lies. I'm watching them. I've got naloxone in the fridge next to the butter.

Manoj Kumar Billigunta

January 23, 2026 AT 08:18 AMI work in a rural clinic in India. We don't have capnography. We don't have continuous monitors. We have nurses who work 16-hour shifts and 3 patients per bed. We use pulse oximeters, but oxygen masks are often reused. I've seen people die because we didn't catch the slow breathing in time. This isn't a US problem-it's a global one. The tools exist, but the will? The funding? The training? We're still guessing. Please don't assume hospitals everywhere are equipped like Johns Hopkins.

Andy Thompson

January 24, 2026 AT 19:28 PMI'm not saying don't use opioids-I'm saying don't trust the system. If you need them, get them, but don't let them control you. And if you're on them, keep a buddy with you. Someone who'll punch you if you don't wake up. That's real medicine.

sagar sanadi

January 25, 2026 AT 06:40 AMSo let me get this straight-you're scared of opioids but not of the 12-hour workdays that make people need them? Or the $10k ER bills that make people choose between rent and pain meds? This whole post is just fear porn. People aren't dying because of opioids-they're dying because they're poor, overworked, and abandoned. Blame the system, not the drug. And btw, 'naloxone on hand'? Cool. But where's the free rehab? The housing? The mental health care? Nah. We'd rather give you a nasal spray and call it a day.

clifford hoang

January 27, 2026 AT 04:59 AMThe real horror isn't the opioid-it's the fact that your body is just a machine that can be hacked by a molecule. Think about it. A tiny chemical bond in your brainstem shuts down your entire respiratory system. That's not medicine. That's biological espionage. And they're using AI now to predict when you'll die? Next thing you know, your smartwatch will beep: 'Warning: Your opioid dosage will cause CO2 toxicity in 14 minutes. Would you like to schedule a funeral?' We're not patients-we're data points in a corporate algorithm. Wake up. You're not being treated. You're being optimized.

Paul Barnes

January 28, 2026 AT 12:43 PMThe post contains several grammatical errors. For instance, 'you might not notice it until it’s too late' should be 'you may not notice it until it is too late' in formal usage. Also, 'their skin might not turn blue' is ambiguous-'their' could refer to 'someone' or 'doctors.' Additionally, the Oxford comma is inconsistently applied in lists. These aren't trivial. Precision matters when lives are at stake.

thomas wall

January 30, 2026 AT 00:03 AMI am utterly appalled that this is even a conversation we must have in the 21st century. To treat a life-threatening physiological collapse as a checklist item is to reduce human dignity to a protocol. These are not statistics-they are mothers, fathers, children-people who trusted the system. And now, we are expected to carry naloxone like a pocketknife because the medical establishment has abdicated its sacred duty. Shame. On. All. Of. Us.

Art Gar

January 31, 2026 AT 12:10 PMThe assertion that 'most patients aren't monitored continuously' is misleading. The CDC and JCAHO guidelines explicitly recommend intermittent monitoring for low-risk patients, with continuous monitoring reserved for high-risk populations. The 96% unmonitored statistic cited refers to non-high-risk patients during non-critical hours. This is not negligence-it is risk-stratified care. The real failure lies in the misapplication of protocols by clinicians, not in the protocols themselves.