Gene Mutations: Simple Guide to What They Are and Why They Matter

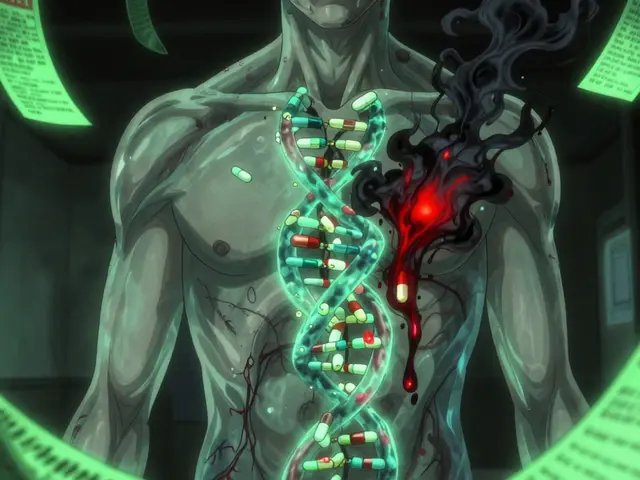

Ever wondered why some people get certain diseases while others don’t? The answer often lies in tiny changes called gene mutations. These are small swaps, deletions, or insertions in our DNA that can change how a protein works. In plain terms, think of DNA as a recipe book – a mutation is a typo that could make the dish taste different or even spoil it.

How Gene Mutations Happen

Mutations can appear in three main ways. First, they can be inherited from Mom or Dad, passed down through generations. Second, they can occur spontaneously when cells copy DNA – a mistake that slips in during the process. Third, external factors like UV light, smoking, or certain chemicals can damage DNA and cause a mutation.

Not all mutations are bad. Some have no effect at all; they’re called “silent” because the protein still works fine. Others are “beneficial,” giving an advantage – for example, a mutation that provides resistance to a disease. The problematic ones are “pathogenic,” meaning they disrupt normal function and can lead to conditions such as cystic fibrosis, sickle‑cell disease, or certain cancers.

Why Knowing About Mutations Helps

Understanding your mutation status can guide medical decisions. If a doctor knows you carry a harmful mutation, they can recommend earlier screenings, lifestyle changes, or preventive medicines. For families with a history of a genetic disorder, testing can reveal who carries the risk and who doesn’t, helping with family planning.

Testing for mutations has become easier and cheaper. A simple blood or saliva sample can be sent to a lab, and results often come back within a week. Many labs now offer panels that look for dozens of common mutations in one go. If you’re considering testing, check that the lab is accredited and that a qualified health professional interprets the results – raw data can be confusing without context.

Knowing your mutation status also opens doors to targeted treatments. Some cancers have drugs that specifically attack cells with certain mutations, like the EGFR mutation in lung cancer. In other cases, gene‑editing technologies are being studied to correct harmful mutations directly, a field that’s still experimental but promising.

So, what should you do next? If you have a strong family history of a genetic disease, talk to your doctor about genetic counseling. Ask about which tests make sense for your situation and how the results could affect your health plan. Remember, a mutation is just one piece of the puzzle – lifestyle, environment, and other genes all play a role in health.

Bottom line: gene mutations are tiny changes in the DNA code that can have big effects. Some are harmless, some help, and some cause disease. Knowing which ones you carry can empower you to make better health choices, catch problems early, and even explore new treatments. Stay curious, ask questions, and use reliable resources – your DNA story is worth understanding.

How Genetics Drive Scaly Skin Overgrowths (Ichthyosis)

Explore how genetic mutations shape scaly skin overgrowths, the inheritance patterns behind ichthyosis, and emerging diagnostic and treatment options.