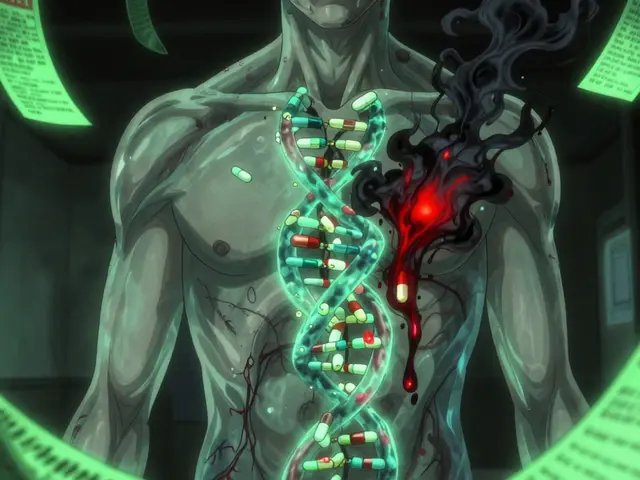

Every year, millions of people take multiple medications at once. It’s common for seniors, chronic illness patients, or those managing mental health conditions to be on five, ten, or even more drugs. But here’s the problem no one talks about: drug interactions aren’t just about what pills you’re taking-they’re also about your genes.

Two people can take the exact same combination of drugs. One gets sick. The other feels fine. Why? It’s not random. It’s not bad luck. It’s pharmacogenomics.

What Pharmacogenomics Actually Means

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect how your body handles drugs. It’s not about whether you’re allergic to penicillin. It’s about whether your liver can break down a drug fast enough-or too slowly-because of the version of a gene you inherited.

For example, the CYP2D6 gene controls how your body processes about 25% of all prescription drugs, including antidepressants, painkillers like codeine, and antipsychotics. Some people have a version of this gene that makes them ultra-rapid metabolizers-they break down drugs too fast, so the medication doesn’t work. Others are poor metabolizers-they process drugs so slowly that even a normal dose builds up to toxic levels.

The FDA has listed over 140 gene-drug pairs with known clinical impacts. That means for more than 140 combinations, your DNA directly affects whether a drug is safe or dangerous for you. And it’s not just CYP2D6. CYP2C19, TPMT, HLA-B, and VKORC1 are just a few others that matter just as much.

How Your Genes Make Drug Interactions Worse

Traditional drug interaction checkers only look at what drugs you’re taking. They don’t know who you are. That’s like checking if two chemicals will react in a test tube-but ignoring whether the test tube is made of glass or plastic.

Pharmacogenomics changes that. It reveals three hidden ways genes make interactions dangerous:

- Inhibitory interactions: One drug blocks the enzyme that breaks down another. If you’re already a poor metabolizer because of your genes, this double hit can cause dangerous drug buildup.

- Induction interactions: One drug speeds up enzyme activity. If you’re a normal metabolizer, that might be fine. But if you’re a slow metabolizer and your body suddenly starts processing drugs faster, the medication stops working.

- Phenoconversion: This is the sneaky one. A drug can temporarily turn your body into a different metabolizer type. Say you’re genetically a fast metabolizer of CYP2D6. But you start taking fluoxetine, a common antidepressant that blocks CYP2D6. Suddenly, your body acts like a poor metabolizer-even though your genes haven’t changed. Your doctor has no way of knowing this unless they check your genetics.

A 2022 study in the American Journal of Managed Care found that when pharmacogenomics was added to drug interaction checkers, the number of clinically significant interactions jumped by 90.7%. That’s not a small tweak. That’s a complete overhaul of risk assessment.

Real-World Examples: When Genetics Save Lives

Let’s look at three real cases where knowing genetics changed everything.

Case 1: Azathioprine and TPMT

Azathioprine is used for autoimmune diseases and organ transplants. But if you have a TPMT gene variant that makes you a poor metabolizer, even a standard dose can destroy your bone marrow. The FDA label says these patients need 10% of the normal dose. Without genetic testing, doctors have no way of knowing. A 2020 study showed that patients with this variant who got full doses had a 60% chance of life-threatening bone marrow suppression.

Case 2: Carbamazepine and HLA-B*15:02

This epilepsy drug can cause Stevens-Johnson Syndrome-a deadly skin reaction. In people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant, the risk is 50 to 100 times higher. The FDA recommends genetic testing before prescribing it to patients of Asian descent. Many hospitals now require it. Skip the test? You’re gambling with someone’s life.

Case 3: Warfarin and CYP2C9/VKORC1

Warfarin, a blood thinner, is notoriously hard to dose. Too little, and you clot. Too much, and you bleed. Studies show that combining genetic data from CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes reduces major bleeding events by 31% and improves time in the safe therapeutic range by 27%. That’s not a marginal gain. That’s a game-changer.

Why Traditional Drug Interaction Tools Fall Short

Most pharmacies and EHR systems use tools like Lexicomp or Micromedex. They list tens of thousands of possible drug interactions. But they don’t know your genes. So they treat everyone the same.

Here’s the problem: 70% of people carry at least one gene variant that affects drug metabolism. But most interaction checkers ignore that. They’ll flag a possible interaction between two drugs-and then give you a warning that applies to everyone. That means doctors get hundreds of false alarms. They start ignoring them.

When you add genetics into the mix, the number of true, high-risk interactions goes up by 34%, according to the FDA’s 2021 pharmacogenomics guideline. That’s not noise. That’s clarity.

Imagine a patient on warfarin and amiodarone. A standard checker flags a moderate interaction. But if that patient is also a CYP2C9 poor metabolizer? That’s not moderate. That’s a ticking time bomb. Genetics turn a yellow alert into a red one.

Where Pharmacogenomics Is Working-and Where It’s Not

Some places are ahead of the curve. Mayo Clinic has been testing patients preemptively since 2011. They’ve found that 89% of patients have at least one actionable gene variant. When their system alerts doctors about dangerous combinations, inappropriate prescribing drops by 45%.

Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program has tested over 100,000 people. They’ve saved lives by catching high-risk combinations before they happen.

But outside of big academic centers, progress is slow. Only 15% of U.S. healthcare systems have PGx testing built into their electronic records. Community pharmacists say 67% don’t have the tools to interpret results. Only 28% feel trained to use them.

And cost is a barrier. A single test can cost $250-$400. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. Only 19 CPT codes exist for PGx testing. Most providers don’t know how to bill for it.

There’s also a glaring gap in research. Only 2% of pharmacogenomics study participants are of African ancestry. That means the guidelines we have? They’re mostly based on white, European populations. For other groups, we’re flying blind.

The Future: AI, Better Guidelines, and Equity

The NIH’s All of Us program has returned PGx results to over 250,000 people. That’s the largest real-world dataset ever collected. And it’s helping fix the diversity problem.

The FDA plans to add 24 new gene-drug pairs to its list in 2024. CPIC is working on guidelines for polypharmacy scenarios-where someone is on five drugs, each affected by different genes. That’s the new frontier.

AI is stepping in too. A 2023 study in Nature Medicine showed an AI model using genetic data improved warfarin dosing accuracy by 37% compared to traditional algorithms. That’s not science fiction. That’s happening now.

The evidence is overwhelming. A 2022 meta-analysis of 42 studies found that PGx-guided therapy reduced adverse drug reactions by 30.8% and improved treatment success by 26.7%. That’s not a nice-to-have. That’s a medical necessity.

What You Can Do Now

If you’re on multiple medications, ask your doctor: “Could my genes affect how these drugs work?”

If you’ve had an unexpected side effect or a drug that didn’t work, even at the right dose-that’s a red flag. It could be your genetics.

Ask if your pharmacy or hospital offers pharmacogenomics testing. Some insurance plans cover it for certain drugs. Others offer it as a one-time test that lasts your whole life.

And if you’ve taken a direct-to-consumer test like 23andMe? You might already have PGx data in your results. Don’t ignore it. Talk to a pharmacist or genetic counselor who can help you interpret it.

Pharmacogenomics isn’t the future. It’s the present. The question isn’t whether it matters. It’s whether you’re ready to use it.

9 Comments

Katrina Morris

January 7, 2026 AT 14:14 PMSo I took 23andMe last year and it said I’m a slow CYP2D6 metabolizer but no one ever told me what that meant until now. I’ve been on sertraline for years and it never worked right-always felt like I was taking sugar pills. Now I get it. My doc just kept upping the dose. I should’ve asked about genetics sooner.

LALITA KUDIYA

January 8, 2026 AT 03:23 AMOMG this is why my uncle died after taking warfarin 😭 we never knew his genes were the issue. Everyone just said it was bad luck. This needs to be standard. Like, right now.

Alex Danner

January 9, 2026 AT 15:36 PMLet’s be real-pharmacogenomics isn’t just the future, it’s the only sane way to prescribe meds in 2024. The fact that we’re still dosing people like they’re lab rats with identical DNA is criminal. I’ve seen patients on 12 meds with zero genetic screening. Half of them are walking time bombs. This isn’t ‘personalized medicine’-it’s basic science. Why is this still optional?

Rachel Steward

January 11, 2026 AT 04:03 AMLet me break this down for the people still clinging to the ‘one-size-fits-all’ delusion. You’re not just ignoring genetics-you’re weaponizing ignorance. The FDA has over 140 gene-drug pairs on record. Your pharmacy’s Lexicomp alert? It’s a child’s coloring book compared to the actual molecular warzone happening in your liver. That ‘moderate interaction’ warning? If you’re a CYP2C9 poor metabolizer on warfarin and amiodarone? That’s not moderate. That’s a death sentence wrapped in a green alert. And yet, 85% of providers still don’t test. This isn’t innovation lagging. This is systemic negligence dressed up as tradition.

Emma Addison Thomas

January 12, 2026 AT 00:59 AMI work in a GP clinic in London, and we just started offering PGx testing for patients on antidepressants. One woman had been on three different SSRIs over five years-each one made her worse. Her test showed she was a CYP2C19 ultra-rapid metabolizer. We switched her to a drug that bypasses that pathway. Within two weeks, she cried during her appointment-not from sadness, but because she’d finally slept through the night in years. It’s not magic. It’s just biology being respected.

Aparna karwande

January 13, 2026 AT 04:30 AMOf course this works-because Western science finally caught up to what Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine have known for centuries: bodies aren’t identical. We’ve been reducing humans to chemical equations while ancient systems saw the soul in the metabolism. Now they want to patent gene tests and charge $400? Meanwhile, in rural India, grandmothers know which herbs to avoid with blood thinners because their daughters died from them. This isn’t breakthrough tech-it’s rediscovery. And the real tragedy? The same pharma companies that profit from polypharmacy are the ones blocking universal testing. They don’t want you to know your genes-they want you to keep buying new pills.

Kamlesh Chauhan

January 14, 2026 AT 09:45 AMbro why are we even talking about this like its new news. i took a dna test in 2018 and it told me i cant take codeine. no one gave a shit. my doctor laughed. now im on tramadol and still in pain because no one cares until you almost die. this is all just corporate lip service. theyll test rich people and ignore everyone else. again. always again.

Anthony Capunong

January 16, 2026 AT 06:59 AMLet’s not pretend this is about science. This is about control. The medical-industrial complex doesn’t want you to know your body’s blueprint because then you’d stop trusting them. Why pay for three different drugs a month when you could pay $300 once and never have another bad reaction? Why let you self-advocate when you can keep being a passive consumer? This isn’t medicine. It’s a revenue model dressed in white coats.

Jonathan Larson

January 16, 2026 AT 07:28 AMWhile the technical and ethical implications of pharmacogenomics are profound, we must not lose sight of the human dimension. The data is compelling, the science is robust, and the moral imperative is undeniable. Yet, the implementation challenges-accessibility, equity, education, and systemic inertia-remain formidable. It is not enough to know that genes matter; we must build systems that ensure this knowledge is not a privilege for the few, but a right for the many. This requires policy, funding, training, and above all, humility from those who hold the power to prescribe. The future of medicine is not in the genome alone, but in how we choose to honor it.